Museum of Welington City and Sea, Wahine Disaster 1968

This is popular Museum tells the stories of

The dramatic story about Wahine Disaster also we can find here. The film about Wahine Disaster showed here. On the morning of 10 April, 1968, Cyclone Gicelle hit

The Wahine had left Lyttelton at 8:40 pm the night before, carrying 610 passengers and 123 crew. There had been storm warnings, but nothing to say that this storm would be any worse than other winds in the strait well known for its rough seas.

The ferry travelled up the east coast of the South Island and headed for

At 5:50 am on the morning of 10 April the captain of the Wahine, Captain Hector Robertson decided to enter the harbour. Twenty minutes later the ferry was alongside Pencarrow Head. The winds had increased to 160 kilometres per hour, and those on board could only see for a distance of 800 metres. On board the Wahine the radar system was no longer working.

A huge wave pushed the Wahine off course and in line with Barrett Reef, and the captain was unable to turn back on course. The force of another massive wave threw him across the bridge of the ship. He decided to keep turning the ferry and try to bring the Wahine around and back out to sea again. For 30 minutes the Wahine fought the waves, but by 6:40 am had been driven back onto the rocks of Barrett Reef.

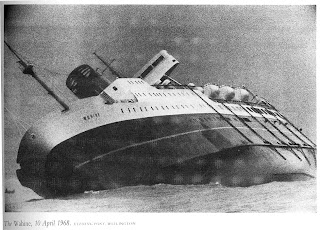

The Wahine founders off Steeple Rock near Seatoun,

Passengers were told that the ferry was aground on the reef, and to put on their lifejackets and report to their assembly points around the ship. The accident was reported to the signal station at

Gradually the Wahine drifted further down the harbour, until she was just by Steeple Rock, off Point Dorset. By now a tug had set off from

Captain Robertson had not considered abandoning the ship earlier because he felt it was safer for the passengers to remain on board, given the storm conditions. But now the order was given to abandon ship. Passengers, not told before how serious the situation was, were now confused and frightened. People slid across the sloping deck, trying to make their way to the lifeboats. Only the four starboard lifeboats could be launched, and crewmen tried to get as many people as possible onto them. One lifeboat was swamped when it hit the water and people were lost into the sea. Some managed to hold onto the boat as it drifted across the harbour to the eastern shore.

Other boats were also swamped but many of the passengers were able to reach the small rescue boats which by now were surrounding the Wahine. Some people tried to make their own way ashore, jumping from the Wahine's decks. Others reached the inflatable life rafts which had been thrown overboard, but several of these were punctured in the wreckage.

The waves of the sea were still battering the ferry, and people in the water struggled to keep hold of wreckage or the sides of the lifeboats. The captain and deputy harbour master were the last to leave after checking that no one remained on the ferry. They were in the water just by the wreck for an hour before being rescued.

At about 2:30 pm the Wahine rolled completely onto her side. By then the first of the survivors were reaching the shore at Seatoun. Rescuers there helped the passengers ashore, not realising the extent of the disaster. Other survivors drifted across the harbour to

0 comments:

Post a Comment